|

Chindu Sreedharan

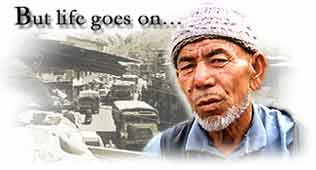

The Old Man of Mingi was at his usual spot. It was here that we had met for the first time a year ago.

"This is Kargil, saab," he sighs. "A place that even God has forsaken."

Actually, this is not Kargil. It is Mingi, 13km away from the town that became famous as the epicentre of last year's conflict. Then, this village doubled as a refugee camp. (Read how it was in Mingi).

People from Drass, Kargil and numerous villages in between had congregated here to escape cross-border shelling. Every house sheltered anything between 20 and 50 migrants.

Today Mingi is normal. Or as normal as it can be under the circumstances. The wave of humanity that descended on it has receded, true. But the winter that just passed was one of discontent.

Sheltering 10,412 refugees had taken its toll. Firewood, as precious as water in this area where temperatures dip to minus 20, was in short supply. There was no electricity till February, and not sufficient food grains either.

More than these, what the people of Mingi feel unhappy about is the way the government chose to ignore their service to the migrants. Over to the Old Man again:

"Only God knows the difficulties we underwent for them," he says. "We don't really mind that. What we mind is that nobody, not even the refugees, thought of thanking us."

Migrants had started arriving in Mingi "by May 9, a Sunday." The bulk remained there for over four months. The state government did provide them ration, but not so much so that the local people completely escaped the brunt.

Many of the migrants had fled their houses in panic. They came without anything, with only the clothes they stood in. Some didn't even have that. There were many without footwear, women without dupattas . The hosts took care of all that.

The migrants were provided free ration till May. They are also being compensated for damage to their property. But the Mingiites, whose life was rudely disrupted by the flood of refugees, were left out in the cold -- without even firewood for their bukharis [wooden stoves].

"We spent what wood we had on the migrants," the Old Man, this voice of the village, says. "We had to cut young trees and burn the wet wood this winter... Chalo, that's all right. But when they went, they forgot to even thank us... They just vanished one by one!"

And the government? As per its records, no shell ever landed in Mingi, no one migrated from here -- so what's all this fuss about?

Compensation can never be adequate

The migrants are all now back home. They returned to find their houses damaged, crops destroyed, livestock missing -- and, in some cases, shops looted.

"There was nothing on my shelves when I came back in September," says Mohammad of Drass.

By then winter had set in. The National Highway 1A was about to close down. There was no prospect of business for another six months.

The winter here, all the way up to Kargil, is so severe that normal life comes to a standstill. The 'earning' months of the people -- mostly farmers -- are, thus, limited to summertime. It was during those months that the Kargil conflict forced them to flee.

Luckily, the government stepped in with ration for the 37,000-odd migrants, fodder assistance for livestock, firewood, and compensation for damage to crop and property.

To date, the authorities have spent over Rs 40 million supplying food to the 4,300 affected families in 44 villages. The dole comprises seven kilos of rice and two kg of flour per person, and 10 litres of kerosene per family.

Besides, the government has also sponsored bunkers. Some 2,000 new shelters have been built in affected villages. In Drass alone 400 new bunkers came up after the conflict.

"Compensation can never be adequate," says Kargil District Commissioner Dr Mohammad Din. "It's a symptomatic relief. Money cannot make up for what they lost."

And it doesn't. There is peace in Kargil town. For the first summer in four years, it is not under shelling. Shops are open, there are people on the road... life looks normal.

But there is an uncertainty, the fear that another round of shelling can start anytime, blanketing the town. Ask anyone about this and he will tell you:

"Who knows what will be? Anything can happen anytime."

The district authorities had their handful during this year's school examinations. There were many attempts at malpractice. The students' plea was that they never got to study because of the conflict.

"Our education system was completely shattered," says Dr Din. "All schools in Kargil had to be shifted to places like Sanku and Khurbatang. But that was no solution. Most students couldn't travel there. The results will not be good."

Kargil won't be caught unawares again

A direct fallout of the conflict is that the government has declared Kargil a civil defence town.

"We now have a foolproof contingency plan in case there's shelling," says Dr Din. "People know what to do in an emergency."

The town has been divided into wards, volunteers are being identified for training in defence drills and a control room is being set up. An air-raid siren has also been activated.

Civil defence authorities in Srinagar say up to 80 per cent damage to life and property can be avoided if people are trained in defence drills.

"For the population of 10,000 in Kargil, a maximum of three civil defence posts with 10 volunteers in each is sufficient," says Home Guards and Civil Defence Inspector General Chaman Lal Banal.

Ironically, Drass and the Mushko valley, which came under even more intense shelling than Kargil last year, have not been give the same status.

No poor district, this

For a district that has survived a conflict and three years of shelling, the economy of Kargil is surprisingly resilient. One indicator of this is cash deposits.

In Drass, for instance, the Jammu and Kashmir State Bank had Rs 26.9 million last year in 2,000 accounts. Now, after the disbursement of compensation, this has swelled to Rs 44 million. This, in a town of 10,000 people.

"There are two reasons for this," says a government official. "One, the lifestyle of the people is very poor, nearly primitive. They are quite happy with the basics of life. Two, they have no avenues to spend money, not even a cinema theatre. So their earnings are all saved."

Ironically, the conflict has opened more employment avenues for the people. The surplus labour from the area, which earlier used to go out to Leh or Srinagar, can now stay put. With its increased presence in the sector, the army now needs transportation, for which they engage civilian trucks and buses.

They also hire ponies and mules to carry stocks to the forward posts in the mountains.

"The army needs porters too," says Dr Din. "You can earn something like Rs 80 for seven to eight hours of walking."

In a town like Kargil that's plenty. Now if only they are allowed to enjoy it in peace...

Additional reportage: Mukthar Ahmad in Srinagar

Concluded

Mail us your comments

Back to Kargil: June 2000

Home

|