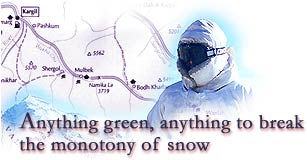

tree. A blade of grass. Anything green.

Just a few days ago, Captain Amit Sharma had craved for greenery. He would have happily given a month's pay for anything to break the monotony of snow that surrounded him. Now that is not so overpoweringly urgent.

Captain Sharma is on his way down. In a little while, he will reach Sando. A more sane, less isolated world. The base camp in Drass is more than 14,000 feet above sea level. That's pretty high all right. But not as high as the forward post he spent the last four-and-a-half months in.

"When I came down the first thing I get is a bunch of flowers. That was kinda good experience, seeing the first flower, the first piece of greenery around here," he says.

"Sitting on the top," he adds, "the only thing you have is the white thing, snow."

Captain Sharma's post is on the Line of Control that divides India from Pakistan in Jammu and Kashmir. Before the Kargil crisis the border here was manned only in summer. The soldiers fell back when the snow set in. The harsh terrain, glaciated at places, avalanche-prone and with temperatures dipping to minus 60 degree Celsius, did their work for them.

This year was different. For the first time, Indian and Pakistani soldiers maintained a strict winter vigil along 150km of border in the Kargil sector. Where there was just one brigade, around 3,000 personnel, there's now some 20,000 soldiers under the newly created 14 Corps. The number of winter defences in the sector has gone up fourfold.

And so, Captain Sharma and his men got to freeze a winter out. In a desert of snow, eyeball to eyeball with the enemy. The Pakistanis too have no choice now but to stay up at the heights.

In such altitude, soldiers normally stay only three months at a time. But Captain Sharma's post was completely cut off. Movement down was not possible till the snows melted.

This morning at 0930 IST he started his descent. It is nearing 1700. He's still walking. Tired and short of breath. But that is how he has been all these days. The thin, oxygen-starved air saw to that. However fit and well acclimatised you are, it will leave you panting in a short while.

"Down here it is almost normal," the captain says. "At the posts, carrying your equipment and walking in the powdery snow, that's really gruelling."

Every step is torture. Every breath an agonising wheeze. You sink into the snow. Despite the imported winter gear, the cold creeps into your bones. And it stays there.

Fortunately for Captain Sharma, the toughest part is over. "I am going on leave," he says, readying for the last leg of his walk. "Want to get home as soon as possible."

But before that, he wants "a nice, huge dinner". And a bit of greenery.

The Pakistani intrusion last May has forced India to man the violated border even in winter. The Kargil sector was under the Srinagar-based 15 Corps till the end of Operation Vijay.

After the conflict a separate wing, the 14 Corps, was formed. Headquartered in Leh, it comprises 3 Infantry and 8 Mountain Division. It is in charge of some 150 km running west from the Zoji La Pass.

The terrain, said to be even worse than Siachen, the highest battlefield on earth, is a waste of knife-edged ridges piercing the sky. Barren and brown in summer, these are powdery and snow-covered in winter.

The altitude ranges from 10,000 feet to 18,000 feet. The average temperature is way below zero. The wind is piercing, powerful. Up at the posts, the air is thin, so thin that even breathing becomes is a major effort.

Such is the border that is being guarded for the first time now. Luckily, the weather gods have been kind. This year the winter was "pretty mild".

"The amount of snowfall even in the most difficult posts was less," says Colonel Ajit Nair (Click for Real Audio), deputy commander of the Kargil-based 121 Brigade. "Consequently winter difficulties, including avalanches, reduced considerably."

"We had expanded our occupations after Op Vijay and in many places the terrain was extremely difficult," he continues. "In a severe winter we would definitely have had many more problems."

The severity -- or, rather, the lack of it -- is reflected in the temperatures of Drass. The lowest the mercury dipped this time in his sub-sector, according to Brigadier G Athmanathan of 56 Brigade, was minus 42 degree Celsius. Being the second coldest inhabited place in the world, a severe winter would have seen it dropping to minus 60 degree Celsius.

This is one reason why winter casualties were much less than the army had anticipated. Plus, the fact that logistics were in place. Winter stocks that went up to the posts this time were 10 times what was sent in the past. Then, there was time for acclimatisation and training.

Yet accidents did happen. Some of the ridges are so sharp that if you miss a step, you end up falling to your death or being buried in snow.

"The men are equipped with avalanche equipment. Each personnel has coloured ropes [which can be used to trace him if he is buried] and avalanche detectors on him," says Brigadier Athmanathan.

Avalanches seem to be the soldier's worst nightmare here. Many areas are prone to it. The army monitors avalanche warnings very closely. The soldiers at the posts, for their part, keep an eye open for any dangerous mass that can come tumbling down.

"What we do is trigger off small avalanches when we see that snow has collected above us," says an officer in the Kaksar area. "We do it either by using dynamite or by firing on it. At some places you can bring it down by simply shouting at it."

Then, the soldiers are vulnerable to other vagaries of the terrain. Besides frostbite, pneumonia and other accompanying ailments, you can get high-altitude pulmonary oedema, the deadly disease that results in an accumulation of fluid in your lungs.

Doctors say it can afflict anyone, however well acclimatised, however fit. And what do you do when it hits you at a forward post, 18,000 feet above, cut off from medical aid? There are special bags -- HAPO bags, these are called -- for that. Once the patient is placed inside, the atmospheric pressure and oxygen content is artificially lowered.

Besides the physical aspects, this winter warfare is a tremendous strain on a soldier's mind. The feeling of physical isolation the posts inflict on its occupants is enough to bring about hallucination, loss of memory and depression.

To combat this, the soldiers are housed in habitats of fibre-reinforced plastic bunkers at the posts. This ensures that four to six men or eight to 10 men stay together. Sentry duty is always in pairs. Post commanders meet the men regularly.

"We try to maintain continuous interaction," says Brigadier Athmanathan. "The moment you see a man is not in his normal state of mind, you talk to him. If that doesn't help, he is turned over."

From certain posts, the men can even phone their relatives. The brigades have also been provided a limited number of INMARSAT telephones. The brigade in Drass has only three. These are rotated among the posts.

Simple things, things that we take for granted, those are the things the men up there crave for. Like fresh vegetables. Or bread. Or telephone. Or a letter from home.

"Seven of our posts were completely cut off in the winter," says an officer at Sando Base. "No coming, no going. Which meant no mail. So they used to read out everybody's letter on the radio."

"At the posts we would keep writing letters and piling them up," he adds. "And then one day the patrol comes and you are happy... if you are lucky you will get to send 10-15 at one go."

Necessity, the cliché goes, is the mother of invention. And the soldiers came up with one of their own to help with the mail.

"What we have here is not email like you but snail mail -- and a little bit of dog mail!" laughs Major S R Das at Sando Base. He has returned from a forward post just the day before.

"You see," he explains, "We had three dogs up there with us. Whisky, Madhuri Dixit and Benazir. These were ordinary dogs. We had picked them up as pups. We tried sending them down with our mail and getting them to fetch it from a camp down."

"Only Whisky succeeded," he continues. "We used to send her down with the mail tied to her neck. Every time she delivered or fetched it she would be rewarded with a tin of kheema!"

Getting mail is the least of the soldier's problem. "We have two enemies here," another major says. "The Pakistanis and the weather."

Among these, the weather seems to be the more nagging. Morning ablutions are public; there aren't permanent toilets in all the posts. Bathing is a weekly affair. And food is mostly out of tins.

"Once I remember, we came to know that they were getting bread to our post," reminisces Major Das. "We came to know of it about a week ago. That whole week was a week of anticipation. I kept thinking, 'I am going to eat fresh bread soon!'"

Ironically, water is a problem at certain posts. There is one such in Drass, for instance. It is glaciated. A soldier has to go down the slope everyday with the help of a rope, completely vulnerable to Pakistani fire, to bring up snow. The Pakistanis use the same source, which is what keeps them from taking a shot at their Indian counterpart.

"One day he may be tempted to try something," sighs an officer. "But you have to go down if you need water."

It is strange. Despite the terrain, despite the strain, there are men who want to go back. Like Major Kartha. He is sitting at a post 18,000 feet high, just 200 metres from the Line of Control. This is his second stint there.

"I think this is the best place to be a commander in," he tells you on the radio. "I am at my viewpoint with my sentry, trying to detect any Paki movement."

"What can you see?"

"I can see a lot of snow around. It is still cold here, less than 10 degrees," he replies. "And I can see the Pakis in their posts. There's only regular movement."

"Is there anything you would wish for, major?"

"No, there's nothing I can think of." A short pause, then his reply. "Actually, I wouldn't mind a few trees around."

Anything green. Anything to break the monotony of the snow.

ON TO PART 2: Toys for General Geek

Mail us your comments

Back to Kargil: June 2000

Home