A lensman's record of

the vale of violence

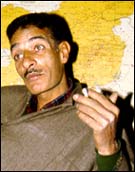

Chindu Sreedharan

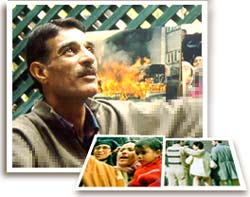

Leaning lightly on a table,

the famous Kashmiri kangri (firepot) in his hands, photojournalist Meraj-ud-din is speaking about Kalashnikovs.

"I think it was in 1987. We were in downtown Srinagar covering a stone-pelting incident when we heard the sound," he says. "We had no idea what it was. Everyone listened... It was the policemen there who told us that it was the Kalashnikov gun."

"Later AKs became a common sight," he continues, "There used to be processions of armed militants. By 1990 in every street, every road, every alley, you would meet 25-30 militant with guns."

Obviously they had the full support of the local people. "Oh, yes," Meraj-ud-din agrees. "The people used to kiss the Kalashnikovs in the militants' hands. And the police used to say, 'Hamare paas aise samaan nahin hai (we don't have such a weapon)."

The 43-year-old Srinagar resident has covered militancy right from day one. Once a government servant, he quit his job to freelance for Kashmir Times in 1979. Two years later he had a lucky break.

While returning from an assignment he got caught in a traffic jam. Minister Ghulam Mohammad came along. He wanted the traffic policeman to stop other vehicles and clear his way. When the cop refused, the minister started slapping him.

"I clicked a series of pictures -- of the minister slapping, the cop clearing the traffic double-quick and then finally saluting the minister!"

The pictures created an uproar. The traffic police struck work. There were questions in the assembly. And Meraj-ud-din was inescapably hooked to the profession. So much so that even when he was injured in a grenade attack he didn't think of giving up his SLR.

"I was covering a strike. The people were pelting the police with stones and I was clicking away," he recollects, "Suddenly I found all the people near me on the ground. There was so much blood... I found my chest bleeding where shrapnel had gone in."

"I was covering a strike. The people were pelting the police with stones and I was clicking away," he recollects, "Suddenly I found all the people near me on the ground. There was so much blood... I found my chest bleeding where shrapnel had gone in."

"That was in 1989. Actually the camera saved my life. Otherwise shrapnel would have entered my face," he adds.

Since that day Meraj-ud-din has seen so much violence that it doesn't move him anymore. Now he is blind to blood. Two incidents, he says, were mainly responsible for this desensitisation: the Gawakadal massacre on January 20, 1990 and the firing on Maulvi Farooq's funeral procession in May the same year.

"When I reached Gawakadal all I could see were the dead. I saw bodies of children, bodies of women, bodies of men..." Meraj-ud-din reminisces. "Later they brought the dead to the police compound. I saw them again. There I cried. I shouted, screamed. Don't do this to the people! That day I saw everything."

That was the last time he cried. "I can't cry now," he says simply, "Mere rishtedaar bhi marte mere aakhon me aasau nahi aate (Even when my relatives die tears don't come to my eyes). My friend died. I didn't cry."

On his neck Meraj-ud-din wears a taveez (talisman). On his person, three identity cards and Sura Yasin, a verse from the Quran.

"The situation is such that you don't know what will happen when. If I get blown up my family should at least be able to identify my body..."

View the vale through Meraj-ud-din's implacable glass eye